在展开对eventlet的学习之前,我们先来学习一下Python的Coroutine。

前情回顾

在这篇文章中,已经学习过了Python中的Generator和yield关键字,如果对生成器和yield还有疑问,可以通过上面的连接回顾一下。

For…example?

这里,就以一个生成器的例子来展开本篇的学习内容吧:def grep(pattern):

print 'Looking for "%s"' % pattern

while True:

line = (yield)

if pattern in line:

print line

首先思考一个问题,执行上面的函数函数的输出是什么?

协程的执行

当我们常用yiled关键字的时候,不可避免的,总会遇到Coroutine,即协程。正如上面的例子,函数能做的不仅是生成值,还可以“消费”(consume)发送给它的值:g = grep('python')

g.next()

Looking for "python"

g.send('Awesome, it is dope!')

g.send('python generators rock!')

python generators rock!

当我们直接调用grep('python')时,什么输出也没有产生,因为coroutine只对next()和send()方法进行响应。即,g.next()时,coroutine开始运行(或者通过send(None)来预启动协程),然后使协程提前执行到第一个yield表达式——line = (yield),此时,协程已经准备好了接收一个值,当我们发送含有python的字符串时,就可以打印出这个字符串。

不过,每次调用.next()有点太麻烦,我们可以用装饰器包装这个coroutine来解决:def coroutine(func):

def start(*args, **kwargs):

cr = func(*args, **kwargs)

cr.next()

return cr

return start

def grep(pattern):

...

协程的关闭

协程可能会无限运行,我们可以使用.close()来关闭。另外,close()是可以被捕获的——通过GeneratorExit异常:

def grep(pattern):

print 'Looking for "%s"' % pattern

try:

while True:

line = (yield)

if pattern in line:

print line

except GeneratorExit:

print 'Going away. Bye!'

不要忽略这个异常,通过上面的写法可以确保coroutine能够正常清理和退出。执行后效果如下:g = grep('python')

g.next()

Looking for "python"

g.send('Awesome, it is dope!')

g.send('python generators rock!')

python generators rock!

g.close()

Going away. Bye!

协程中抛出异常

在协程中,是允许抛出异常的:g = grep('python')

g.next()

Looking for "python"

g.send('Awesome, it is dope!')

g.send('python generators rock!')

python generators rock!

g.throw(RuntimeError, "It's a RuntimeError!")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 4, in grep

RuntimeError: It's a RuntimeError!

注意,异常是在yield表达式处产生的,而且跟普通异常一样是可以被捕获和处理的。

简单梳理一下

经过上面的例子,我们可以简单的梳理如下:

- Generator产生数据用于迭代

- Coroutine是数据的消费者

- 不要把这两个概念弄混

More, I want MORE!

通通连起来

Coroutine还可以用于构造pipeline(管道),即把好多coroutine连起来,通过send()方法来传递数据。

对于pipeline来讲,我们需要一个函数来驱动,我们暂且称之为source。另外还需要一个端点(end-point)来终止整个管道,我们暂且称之为sink,下面举个例子,用coroutine写一个类似tail -f的功能:def follow(the_file, target):

# Go to the end of the file

the_file.seek(0, 2)

while True:

line = the_file.readline()

if not line:

time.sleep(0.1)

continue

target.send(line)

def printer():

while True:

line = (yield)

print line

if __name__ == '__main__':

f = open("data.txt")

follow(f, printer())

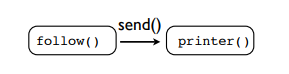

这样,我们在执行时,打开data.txt写入信息,就会在控制台看到输出。在这个例子中,follow()用于逐行读取,然后把数据发送到printer()协程中,过程如图:

在这里,source就是follow(),sink就是printer()。

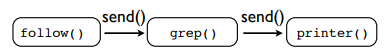

管道中的过滤器

在这个例子基础上,我们还可增加一个协程用做过滤器(filter),只要对对前面的grep()稍作改造,然后调用的时候注意一下:

def grep(pattern, target):

print 'Looking for "%s"' % pattern

try:

while True:

line = (yield)

if pattern in line:

target.send(line)

except GeneratorExit:

print 'Going away. Bye!'

if __name__ == '__main__':

f = open("data.txt")

follow(f, grep('python', printer()))

启动后,grep()这个协程负责只有在data.txt中写入行含有python才会把当前行数据发送到printer(),由其在控制台打印出来,过程如图:

注:coroutine和generator的关键区别在于生成器使用迭代器在管道中拉取数据;协程通过send()向管道中推送数据。

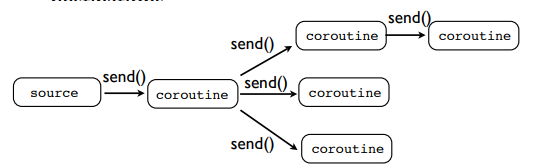

管道连接更多的管道

有了协程,我们可以将数据发送到更多的地方……

那么我们就来一个🌰,下列代码实现了一个广播的coroutine,将数据推送到批量的coroutines中:

def broadcast(targets):

while True:

item = (yield)

for target in targets:

target.send(item)

根据调用方式的不同,实际上会产生两种效果广播的情况——

①发送到不同的printer()follow(f, broadcast([grep('python', printer()),

grep('hello', printer()),

grep('world', printer())])

)

②发送到相同的printer()p = printer()

follow(f, broadcast([

grep('python', p),

grep('hello', p),

grep('world', p)]))

不过在本例中,效果是一样的……

从数据处理到并发编程

到目前为止,我们前面聊的coroutine的应用都是在处理数据,那么如果我们把数据发送给线程、发送给进程……协程程序自然而然就会涉及到线程和分布式系统的问题。

看到这,估计也累了,那暂且先挖个坑,未完待续……